The History of the Guild

Ruskin announced the formation of St George's Company, as it was first called, in 1871, but it was not till 1878 that it was properly constituted and given its present name. In its origins, it was a frankly utopian body. It represented Ruskin's practical response to a society in which profit and mass-production seemed to be everything, beauty, goodness and ordinary happiness nothing.

Ruskin announced the formation of St George's Company, as it was first called, in 1871, but it was not till 1878 that it was properly constituted and given its present name. In its origins, it was a frankly utopian body. It represented Ruskin's practical response to a society in which profit and mass-production seemed to be everything, beauty, goodness and ordinary happiness nothing.

Ruskin made it clear in a monthly series of 'Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain' called Fors Clavigera (read online) that the ambitious aim of the Guild was to make Britain a happier place to live in. 'I have listened to many ingenious persons,' he wrote, 'who say we are better off now than ever we were before' but (he went on) 'we cannot be called, as a nation, well off, while so many of us are living... in... beggary.' In other words, for Ruskin, no nation should be called rich if its cities were ugly, its countryside polluted and its people poor, hungry and ignorant, and he asked those who agreed with him to join in 'establishing a National Store instead of a National Debt'.

In practice the Guild's efforts were focused on quite modest ideals. He targeted three main areas of English life in need of support and improvement: art education; craft work; and the rural economy. He hoped to promote the understanding and appreciation of good art, to encourage craftsmanship rather than mass production, and to revive what we should now call sustainable agriculture and horticulture. He was trying to create, in effect, an alternative to industrial capitalism. In some ways, as the word 'Guild' suggests, he looked back to certain values of the past, particularly of the Middle Ages, but he combined those values with a belief in social improvement. St George's communities were to be based on the land and on agricultural labour, but they were also to include schools, libraries and art galleries, so that Companions, as members of the Guild are still called, worked with their hands and cultivated their inner lives.

Soon after founding the Guild, Ruskin suffered a series of psychological breakdowns, as a result of which his great ambitions were never really fulfilled. But the things he did achieve continue to inspire his successors. Today, the Guild strives harder than ever to put his plans into effect.

AN EDUCATIONAL MUSEUM

Ruskin's admiration for the Sheffield iron workers led to the establishment in 1875 of the Guild's first museum. which was situated in the Walkley area of the city (the museum has been re-created online, here). Ruskin's hope was to better the lot of the workmen who visited it by providing education, stimulation and inspiration. The small house in Walkley (seen today from Bole Hill Road and marked with a Guild-commissioned plaque) was filled with commissioned copies of Old Master paintings, studies of architecture, beautiful geological specimens, casts of sculpture, medieval manuscripts, rare printed books and a library of standard works. These exemplary artefacts, precious objects and works of art were later housed in Meersbrook Hall, briefly went to Reading University, then returned to Sheffield to premises in Norfolk Street. Known today as the Ruskin Collection, it remains in the city centre, free and open to the public in a dedicated gallery in Museums Sheffield's Millennium Gallery.

The proposal to build a museum at Bewdley never materialised but plans were drawn up. Today, the Guild supports the town's museum with occasional loans, and the Anthony Page Collection of Ruskin books is also available for consultation there. Find out more here.

EARLY COMPANIONS

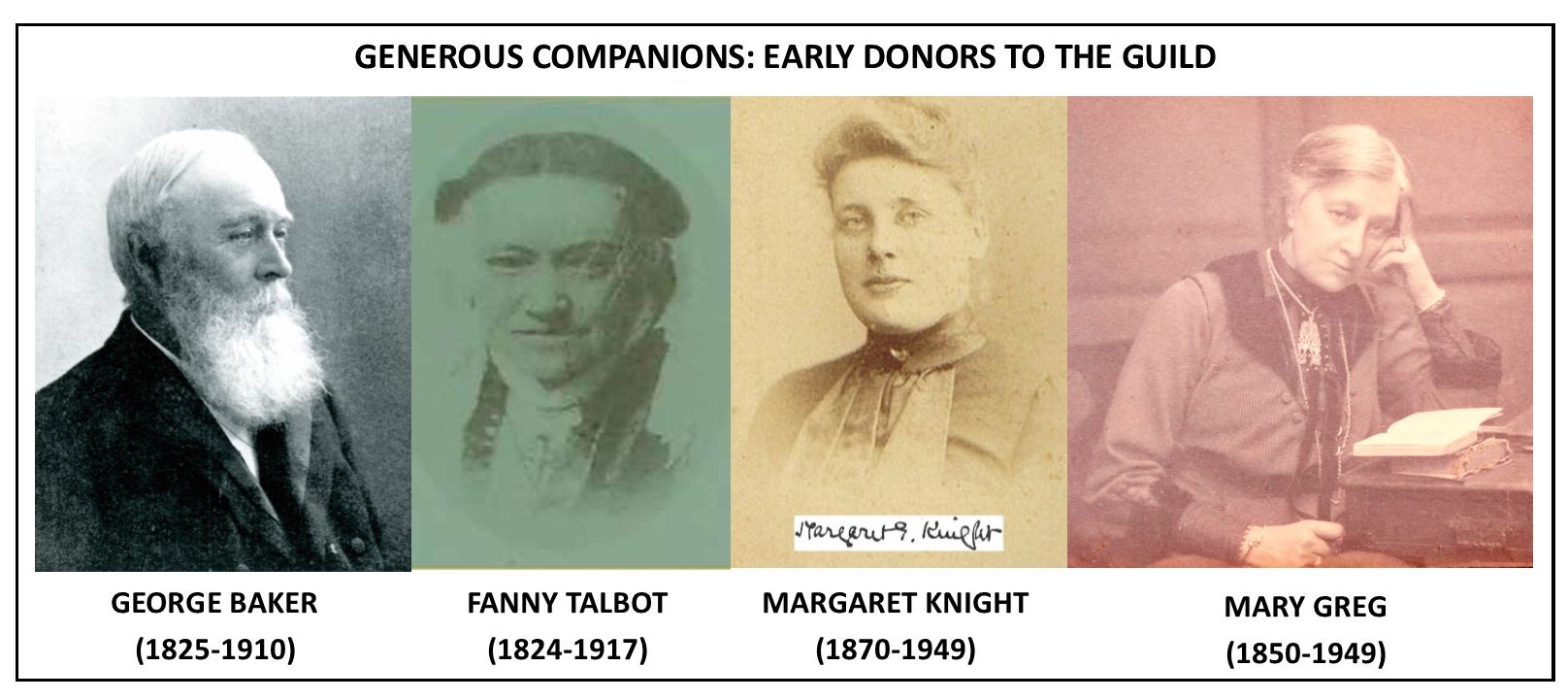

Early Guild members—called 'Companions'—supported Ruskin's endeavours with gifts of land and money. A farm was purchased in Totley, Sheffield (subsequently sold); woodland was given by George Baker in the Wyre Forest near Bewdley, Worcestershire; and a number of houses in Barmouth, Wales were donated by Fanny Talbot (subsequently sold). Later, Margaret Knight entrusted a wildflower meadow in Sheepscombe, Gloucestershire to the Guild, and Mary Greg—who also donated generously to the Ruskin Collection, notably her own amateur nature diaries—bequeathed houses in Westmill, Hertfordshire.